By Susan Pedwell

Hospital nursing schools trained nurses in how to care for the sick. In 1920, U of T turned that training upside down. It began educating nurses in how to prevent sickness by promoting health.

In the preceding years, the Spanish Influenza pandemic had wiped out about four per cent of the world’s population. The flu hit Toronto particularly hard in October 1919, killing 1,300 citizens in just one month.

The Canadian Red Cross Society was impressed by the contributions that public health nurses were making during the pandemic. Believing that a “well-staffed nursing service is an important factor in the health and happiness of the Dominion,” it spearheaded an initiative to educate more nurses for the public health field.

In 1919, the provincial branches of the Canadian Red Cross Society approached five universities, each in a different province, to offer financial support for educating graduate nurses in public health. The Ontario Red Cross Society offered U of T the financing to run a program for three years. U of T accepted the grant and ventured into nursing for the first time by establishing the Department of Public Health Nursing.

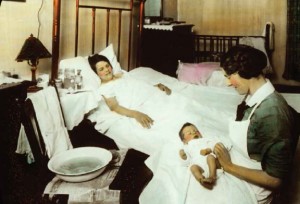

Of the 50 nurses who enrolled in the program’s first year, more than half were First World War veterans. In Europe, the “nursing sisters” experienced much hard-ship, but also much responsibility. Back home, if they returned to hospital work they would return to passivity, subservience and unquestioning obedience. Public health nurses, though, were free of the hospital’s rigid hierarchy although still constrained by local physicians and health boards. But armed with a briefcase of pamphlets, they could independently visit new mothers at home, speak about safety to children in their classrooms and encourage communities to develop healthy habits.

Under the leadership of Kathleen Russell, our inaugural director, U of T’s public health nursing program was soon being held up as a model of excellence across Canada. The department’s one-year certificate program included six months of course work in subjects such as hygiene, social work theory and “teaching procedure.” The program also included placements with several agencies, including the Toronto Department of Public Health and Victorian Order of Nurses.

The U of T program caught the eye of the Rockefeller Foundation in New York City, which was also interested in preparing nurses for public health services. In 1923, the foundation started sending international fellowship students to U of T to take our public health nursing program.

From the day Russell arrived, she worked toward shaping the department into a full-fledged faculty of nursing. In brief, Russell, with her golden hair bobby-pinned into an elegant chignon, came in fighting. She fought for nursing as a legitimate course of university study. She fought against opposition toward women earning a university education to prepare them for a professional career.

U of T saw the three years of nursing that the Red Cross had funded as a temporary endeavour. Russell, though, likely saw it as a respectable beginning. By the time the Red Cross funding ended in 1923, Russell had persuaded the university to finance U of T Nursing. She had also persuaded the Rockefeller Foundation to give U of T’s fledgling nursing program the largest donation awarded to any nursing school outside the United States. The funding provided U of T Nursing with more security – not to mention more prestige – than any other university nursing program in Canada.

This story first appeared in the Fall/Winter 2014 issue of Pulse Magazine.