by Susan Pedwell

Your day isn’t starting well. This morning you couldn’t find your car keys. You ransacked your home trying to locate them only to discover them jingling in your pocket. Then on the way to work, you remembered you left your lunch box on the kitchen counter.

How many hours did you sleep last night?

Oh. Your child woke you up at midnight. Again?

“Sleep is critically important for families,” says Robyn Stremler, a Bloomberg Nursing associate professor who researches how to improve sleep and health outcomes in infants, children and parents, through pregnancy and beyond. “Not getting enough sleep has multiple effects on physical well-being, emotional resilience and cognitive performance.”

Name that sleep deprivation

Adults need to sleep seven to nine hours a night. Any night you get less than six hours of shuteye, you suffer acute sleep deprivation. “You start to see changes – not only in increased daytime sleepiness, but your mood and decision-making abilities decline,” says Stremler, PhD 2003.

If you have several nights with less than six hours of sleep, you enter the realm of chronic sleep deprivation, which compromises your immune function, making you susceptible to every cold and flu bug that crosses your path. Worse yet, over the long term it can affect your cardiovascular, metabolic and mental health.

Expecting slumber

When Stremler was a postpartum nurse at the Jewish General Hospital in Montreal, she was struck by how many women arriving to give birth were sleep deprived. “Sleep complaints are common in pregnancy, especially in the third trimester,” she says. “Health care providers haven’t been able to offer any real solutions, they just shrug their shoulders because losing sleep in pregnancy is such an expected event.”

Dr. Stremler is bent on changing that. As part of her Sleep Tyme Study, she surveyed 498 women before and after giving birth to examine the psychological and lifestyle factors contributing to sleep loss in pregnancy. She also wanted to substantiate evidence that sleep problems during pregnancy may increase a woman’s risk of preeclampsia, C-section and depression, and affect the health of her unborn child.

Precious baby, precious sleep

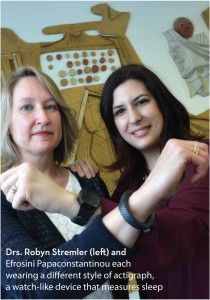

Caring for an infant whose sleep isn’t consolidated at night means new parents have acute if not chronic sleep deprivation. In a recent investigation of 246 new mothers, Stremler studied how infant sleep location affects maternal sleep. By asking the women to wear an actigraph, a bracelet-like device that measures sleep, Stremler was able to calculate how the mother slept when the infant slept with the parents, in a separate bed in the parents’ room or in a separate room.

While many parents believe they’ll get more sleep if they just take their baby to bed with them, Stremler found the opposite: “With the baby in bed, the mothers had more awakenings and shorter stretches of sleep, which may prevent them from entering deeper, more restorative sleep. Restorative sleep requires at least 90 minutes of uninterrupted sleep.

“Around the world, there’s a wide variation in how involved parents are in helping their infants fall asleep,” she continues. “Some families rock their babies to sleep and value not letting them sleep alone. Other families want to work toward their child falling asleep independently.

“I see a trend toward parents using sleep training methods to get infants to fall asleep on their own too early. While you can try to gently shape your baby’s sleep by putting him or her down drowsy but awake in the first few months, most health care professionals agree you shouldn’t try to implement a sleep-training regimen before six months.”

Child of mine

Newborns aren’t the only ones interrupting a family’s sleep. “Children with a neurodevelopmental disorder or chronic illness are more likely to have sleep problems,” says Stremler. “And adolescents don’t sleep as much as they should. Studies show that 60 per cent don’t get the nine hours a night they need.

“My biggest piece of advice for families is to make sleep a priority. Children model their parents.” But if the kids are modelling Mom, there could be a problem. An American study found that women put sleep near the bottom of their list of priorities, far below their children, other family members, leisure time and career.

Even Stremler – a wife, mother, professor and sleep proponent – occasionally doesn’t get the seven to nine hours of sleep a night she knows she needs. “Last night, I went grocery shopping after putting my kids to bed so I only got six hours of sleep,” she admits. “Getting enough sleep is tough.”

Why don’t you just go home?

When you see exhausted parents attempting to sleep in their child’s hospital room, you may want to encourage them to head home for a good night’s sleep. But in the first formal research study to examine the sleep of parents of hospitalized children, Associate Professor Robyn Stremler found that parents sleep better when they’re close to their child. “The parents who slept at home or in a hotel woke more times per night than those who slept in a hospital lounge or waiting room,” she concluded.

When you see exhausted parents attempting to sleep in their child’s hospital room, you may want to encourage them to head home for a good night’s sleep. But in the first formal research study to examine the sleep of parents of hospitalized children, Associate Professor Robyn Stremler found that parents sleep better when they’re close to their child. “The parents who slept at home or in a hotel woke more times per night than those who slept in a hospital lounge or waiting room,” she concluded.

Stremler believes parental sleep in hospitals needs more attention. “These parents are expected to understand and retain complex information about their child’s diagnosis, prognosis and progress. Sleep is important for their ability to cope with the illness, support their child, participate in decision-making and maintain relationships.”

Children’s sleep in hospitals is also of concern. For her doctoral dissertation, one of Stremler’s students, Efrosini Papaconstantinou, developed an innovative program to improve the sleep of paediatric patients during hospitalization and once discharged home. Papaconstantinou’s “Relax to Sleep” intervention included a discussion and booklet on sleep, and a relaxation breathing exercise for the child.

Compared to the control group, the children who had the intervention averaged 50 more minutes of night-time sleep while in the hospital. And after being discharged, they had less sleep disturbance. “The hospital environment is not conducive to sleep, and yet sleep is vitally important for recovery,” says Papaconstantinou, PhD 2014.

This story originally appeared in the Spring/Summer 2015 issue of Pulse magazine.